Machine Learning may lead to unfairness

Fairness in machine learning - the case of juvenile criminal justice in Catalonia

In the HUMAINT project we deal, among other things, with the issue of fairness in machine learning, which plays a big role in research communities such as FAT-ML (a workshop organized within the ICML conference) and FAT* (the main conference on this topic). Many of the papers in this field are interdisciplinary, authored by researchers from computer science, social sciences, economics or law. Part of the papers focus on developing fair machine learning systems, understanding the causes of unfairness, and, since it’s a new field, framing the problem correctly for different areas/systems.

We presented our paper on fairness in juvenile criminal justice (the Catalonian SAVRY)at the International Conference on AI and Law, where it has received the best paper award:

Songül Tolan, Marius Miron, Emilia Gomez, Carlos Castillo, “Why Machine Learning May Lead to Unfairness: Evidence from Risk Assessment for Juvenile Justice in Catalonia”

In this paper we analyze a tool and several machine learning models designed to predict reoffense risk of defendants in prison in terms of predictive performance and fairness. However, we do not stop there. We use interpretable machine learning to trace back discrimination by assessing which features were important when the algorithm was correct or wrong with a category of people (here, foreigners).

Machine learning for decision making

When judges decide whether to detain or release defendants awaiting trial, they must consider the defendants flight risk or the likelihood to reoffend. The act of reoffense after being convicted for another crime in the past is also termed recidivism. Increasingly, criminal justice systems use algorithms to support judge decisions with machine predictions of recidivism risk. These algorithms derive their rules from data on past cases, corresponding information on judge decisions and information on recidivism (usually we allow up to two years after the exit from prison). We evaluate the performance of of algorithmic and human decision making on splits of the same data to tell whether the decision was correct or not.

There are various reasons why we would like to have a machine learning model support decision making: judges are human and humans have biases, as shown in this book. On the other hand, there are reasons why we should be careful when considering the support of machine learning systems: machine learning models inherit human bias (mostly through data). Technology is not value-neutral and it’s created by people who express a set of values in the things they create. Often this has unintended consequences, such as discrimination. Each data point in a dataset represents a criminal case which is characterized by a set of features. Machine learning models learn from these features to separate between recidivists and non-recidivists.

What features did we use to predict recidivism in this case?

Age at main crime, sex, nationality, sentence, previous number of crimes, year of crime, whether probation was given or not etc. These are features related to demographics and criminal history and we represent them with red.

The literature on fair algorithms mainly derives its fairness concepts from a legal context. Generally, a process or decision is considered fair if it does not discriminate against people on the basis of their membership to a protected group, such as sex or race. In this case we tested for discrimination against foreigners and on the basis of sex. We detect discrimination in a decision making process (indipendent of a human or algorithmic origin) by testing the decision against a “ground truth”(e.g. recividism occured within two years after release date or not). Processes that are overproportionally correct or wrong for a particular protected feature indicate discrimination. Risk assessment tools Tools which assist decision makers are nowadays used in criminal justice, medicine, finance etc. One of the well known tools for recidivism prediction is COMPAS, which stirred some controversy a while ago because arguably it discriminates against African-American people.

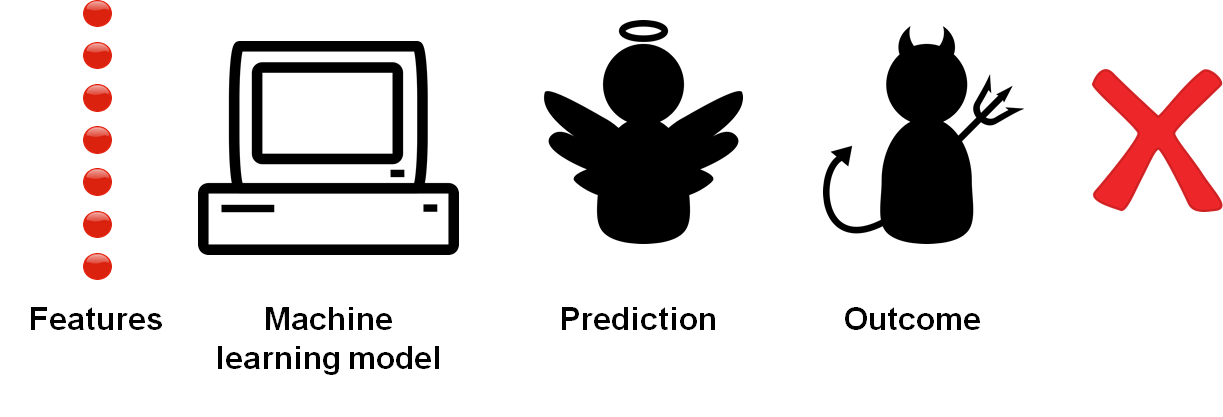

SAVRY stands for Structured Assessment of Violent Risk in Youth and it’s used in many countries across the world to assess the risk of violent recidivism for young people. It has been mainly designed to work well for violent crimes and male juveniles. In contrast to COMPAS, SAVRY is a transparent list of features/terms,and the final risk evaluation remains at the discretion of the human expert..

What features do we have in SAVRY?

SAVRY is based on a questionnaire which collects information on: early violence, self-harm violence, home violence, poor school achievement, stress and poor coping mechanisms, substance abuse, criminal parent/caregiver. However, SAVRY is expensive, as it requires the expertise and the time to gather all that data. We wanted to see if machine learning models are better in predicting recidivism and if they exhibit any discrimination, in comparison to SAVRY. Experiments In terms of input features we test the following three sets:

Static features (demographics and criminal history features) - red features

SAVRY features - blue features

Static + SAVRY - red+blue features

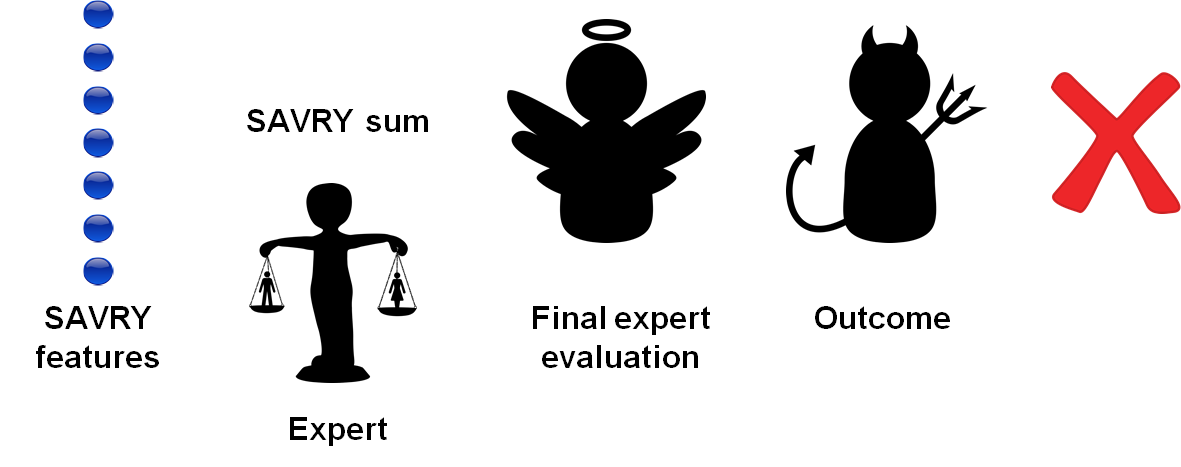

In terms of machine learning methods, we tested logistic regression, multi-layer perceptron, svm, knn, random forest, naive bayes to report predictive performance (area under the curve), but we stayed with the top two performing ones to evaluate fairness (logistic regression and multi-layer perceptron).

The dataset we used in our experiments comprises 855 juvenile offenders aged 12-17 in Catalonia with crimes committed between 2002 -2010. The release was in 2010 and the recidivism status was followed up in 2013 and 2015.

In our experiments the SAVRY Sum (0.64) and Expert (0.66) have a lower predictive power (lower AUC) than the ML models.

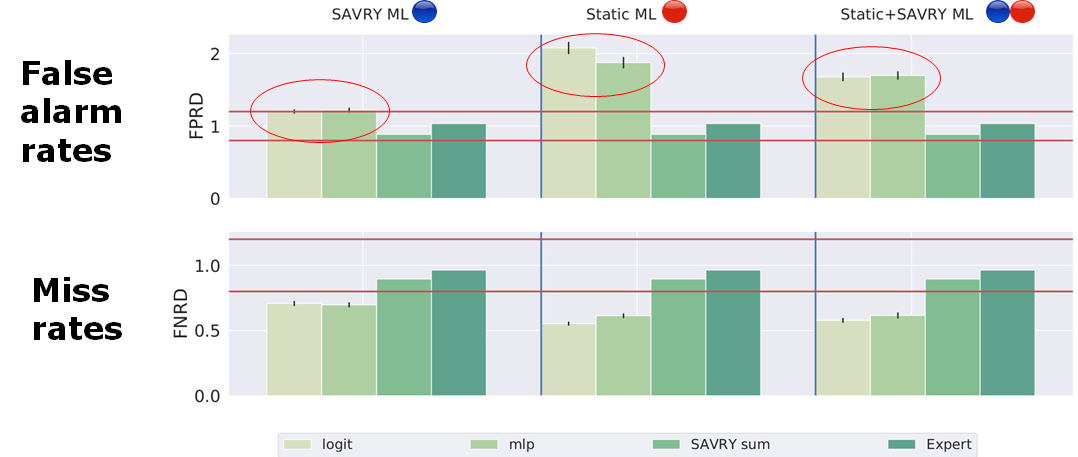

However, when looking at the classification errors done with respect to foreigners (false positive rates for foreigners compared to false positive rates for Spanish), ML is generally more unfair.

In fact, the more non-SAVRY features (red) you introduce, the more you increase the disparity between Spaniards and foreigners. Not using non-SAVRY features is still discriminative (first two bars in the first column) which was expected: many state of the art papers report discrimination even in the absence of problematic features.

The difference between the three sets of features led us to analyze the importance of the features by using machine learning interpretability. With respect to that, while some models are interpretable by definition, for other black-box models we need post-hoc methods which can give an approximate interpretation. One of these frameworks, possibly the most used is LIME.

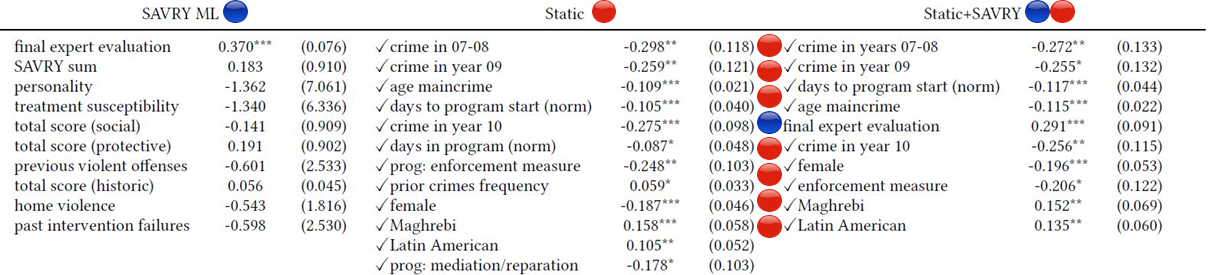

For logistic regression the importance is given by the weights learned by the model:

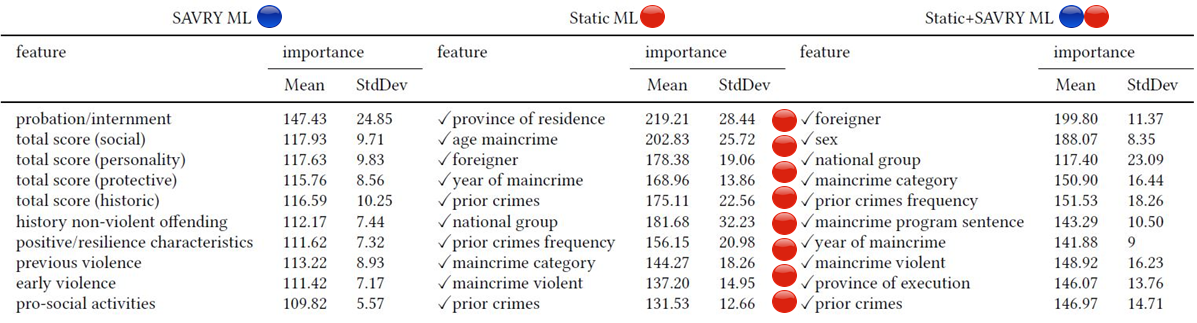

For multi-layer perceptron, LIME yields the following global importance:

Note that when you combine non-Savry (red) and SAVRY (blue) features, the model relies more on the non-SAVRY features on demographics and criminal history.

As we mentioned, not using the red features has lead to discrimination. This made us think that the causes of discrimination do not lie in the features but in the data itself. It is established in the literature that one of the important sources of discrimination is data itself. A good indicator of this is the difference in prevalence of recidivism also termed “base rates” between Spaniards and foreigners. Basically, if 46% of the foreigners in your dataset are recidivists compared to solely 32% of the Spaniards, then your model will learn that the features correlated to being a foreigner are important. Such a model will yield more false alarms with respect to foreigners.

Therefore, we conclude that algorithms that predict recidivism in criminal justice should only be used under the awareness of such fairness issues.

BLOG

research, news, machine learning, fairness, bias